Jam to-day

Recently

I listened to an On Being segment

interviewing Rex Jung, a neuropsychologist and creativity researcher, in which

he discusses, among other things, transient hyperfrontality, that brain

state in which we are most apt to make connections between the seemingly

unrelated to innovative effect. He had a useful metaphor for this

brain state, comparing our usual brain function to a super highway, and

transient hyperfrontality or, the down

regulation of the frontal lobes, to the back roads, or even the dirt roads,

where our minds wander freely. This is not “knowledge acquisition,” but rather a kind of deep, undirected processing that

creates something new and useful

(which, for many neuropsychologists, is the working definition of creativity).

We all have our own ways of getting there, he notes: walking, yoga, napping, driving, rearranging the paperclips on our desk.

I wrote a

poem about it once…

Tennyson Walked

In the bizarre rituals of the batter

I see the writer at her early morning desk

Herding the paper clips,

Aligning the research stacks, just so

To create a path perhaps, a sight line,

A semblance of a clear-cut open path.

Virginia Woolf cleaned the house first,

Tennyson walked.

A rite of order and approach that,

On more than one occasion

Allowed them to hit it out of the park.

Anyone

immersed in the novel writing process, particularly the research/exploration

end of novel writing, is familiar with the strange, out-of-time, connectivity

that seems to arise from this kind of creative work. Associations multiply.

Dramatic coincidences abound. Jung called it “synchronicity”, temporally

coincident occurances of acausal events. It is an odd state, where unrelated events or

circumstances become meaningful and often symbolic. For the writer deeply

engaged with theme and storyline, it’s a familiar sensation; the

roots and branches of research are endless, and significant connections grow

and multiply.

This is

the way the writer’s brain works, by association,

and it was with great relief that I came to realize that what I considered my

scattered, undisciplined, illogical processing was, in fact, a boon to the

artist, a state of mind to be prized

and cultivated. We are all our own libraries, after all, our psychological and

emotional and intellectual shelves stacked high from birth, in our own quirky

systems, with all we hold meaningful.

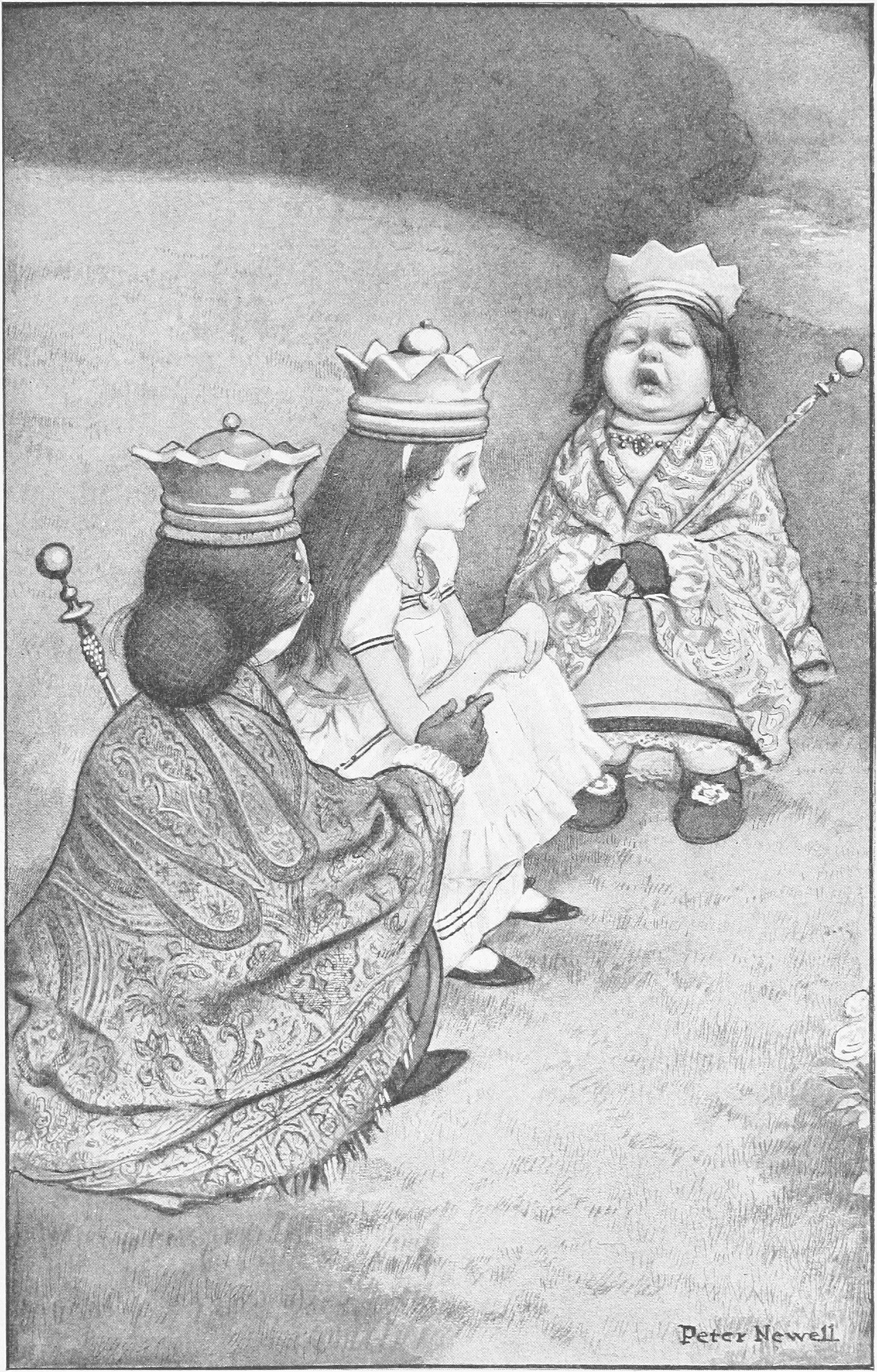

'The rule is, jam tomorrow and jam

yesterday--but never jam to-day.

'

'It MUST

come sometimes to "jam to-day,"' Alice objected.

'No, it

can't,' said the Queen. 'It's jam every OTHER day: to-day isn't any OTHER day,

you know.

'

'I don't

understand you,' said Alice. 'It's dreadfully confusing!'

'

‘That's the

effect of living backwards,' the Queen said kindly: 'it always makes one a

little giddy at first—

'

'Living

backwards!' Alice repeated in great astonishment. 'I never heard of such a

thing!'

'

--but there's

one great advantage in it, that one's memory works both ways.

'

'I'm sure

MINE only works one way,' Alice remarked. 'I can't remember things before they

happen.

'

'It's a poor

sort of memory that only works backwards,' the Queen remarked.

Lewis

Carrol, Through The Looking Glass